NASA is on the verge of a phenomenal mission with the “Habitable Worlds Observatory,” a telescope designed to identify and directly image potentially habitable exoplanets. Backed by funding from the Decadal Survey in Astronomy and Astrophysics of the National Academies, this mission seeks to investigate the possibility of life beyond our planet. One of the intriguing features of this observatory is its ability to search for artificial “city lights” on the nightsides of these distant worlds.

Habitable Worlds Observatory: A new era in exoplanet research

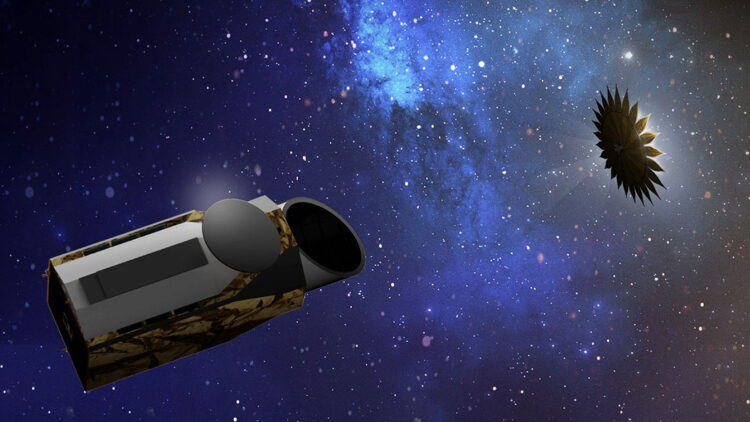

The Habitable Worlds Observatory will be the first telescope exclusively dedicated to the search for extraterrestrial life. Employing cutting-edge spectroscopy techniques, it aims to identify molecular signatures of life, such as oxygen and methane (known as biosignatures).

To address the mission’s challenges, NASA has recently selected three industry proposals to support the mission’s requirements, allocating $17.5 million for this purpose. This includes the development of a high-performance coronagraph to block out starlight, enabling clearer imaging of distant planets.

Additionally, the observatory may detect artificial light emitted from the nightsides of potentially habitable exoplanets. A study co-authored by researcher Elisa Tabor suggests that the telescope will be sensitive enough to detect this light comparable to the starlight on a planet’s day side. This feature allows the telescope to spot city lights, as well as distinguish between different types of light sources that alien civilizations might use, such as LED lamps.

Detection does not necessitate imaging the planet directly; it merely involves observing the light contributions from the planet along with the star’s emissions. As the planet rotates and its orientation shifts relative to the observer, changes in light intensity can reveal the presence of artificial illumination.

NASA is now targeting Proxima Centauri

The greatest chances of detecting city lights beyond our solar system lie in the vicinity of the nearest stars.

Take Proxima Centauri, for instance: it’s a red dwarf located just 4.25 light years away and is considerably dimmer than the Sun. This means that any habitable planet would need to orbit much closer to sustain conditions suitable for life.

Proxima Centauri hosts a rocky planet known as Proxima b, which is at least 1.3 times the mass of Earth. Due to its close proximity to its host star, Proxima b is believed to be tidally locked, resulting in one side experiencing perpetual daylight while the other remains in darkness.

If a technologically advanced alien civilization exists there, the day side might be equipped with photovoltaic cells to produce power, potentially illuminating the cold, dark nightside.

The exciting possibility of discovering life on other planets

The Habitable Worlds Observatory could possibly detect city lights on the permanent nightside of Proxima b, even if those lights are as dim as those found in our current urban environments. The telescope’s sensitivity is such that it allows it to pinpoint specific light frequencies that are much narrower than the full spectral range of Proxima Centauri’s emissions.

If Proxima b shows no signs of technological life, the observatory will continue its search for city lights around other nearby stars, such as Alpha Centauri A & B, Barnard’s Star, and much more.

Furthermore, it could detect artificial illumination from advanced spacecraft traversing interstellar space, thereby expanding the scope of our cosmic explorations.

As NASA prepares to launch this incredible observatory, the potential of this telescope is certainly immense. This mission not only holds the promise of finding life but also offers a glimpse into the possible technological advancements of other civilizations. Through this observatory, soon we might be able to observe cities on far-off worlds that we have yet to discover.